When I was a governess there, all the castle buildings were painted yellow with white trim, as seen in the building on the right (once a barn, but now a convention center). Then it was time to repaint. Since it was a historic building, dating from the 15th century, the government was involved.

During the process, they discovered that the original paint job had been white with gray accents. All the yellow paint had to be meticulously removed to expose the original surface. Government regulations require that the new paint job be the same as the original.

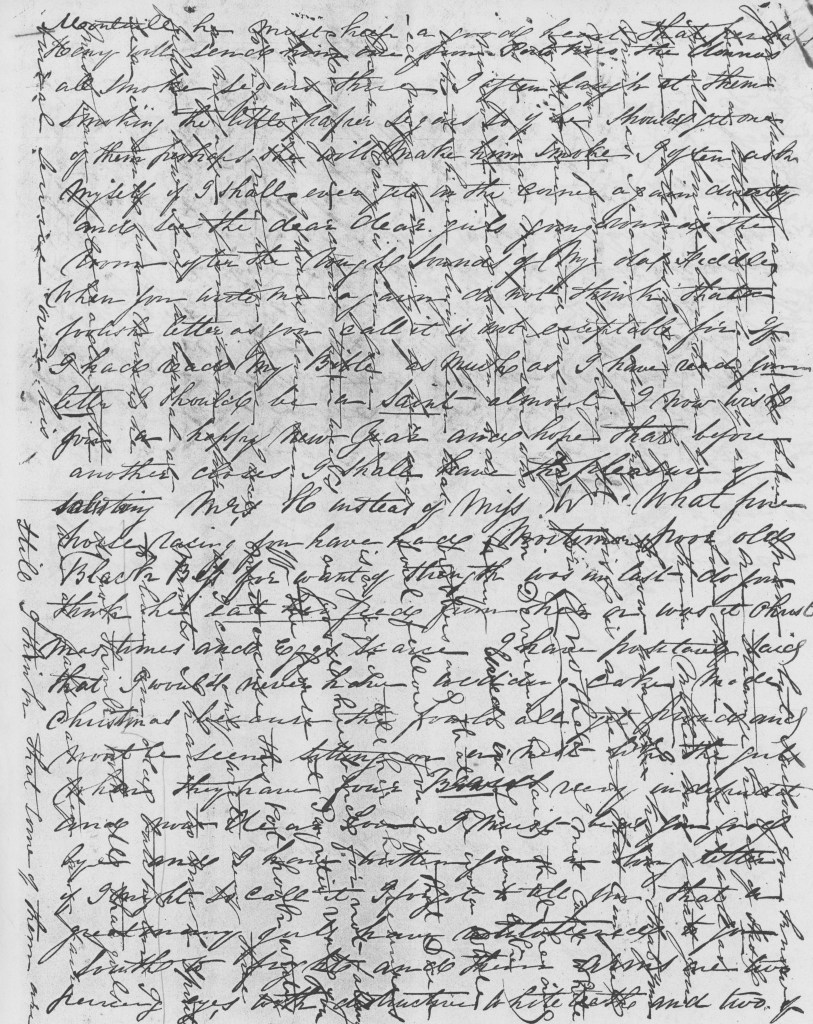

This photo shows the east façade of the castle, with the entry arch to the courtyard, after the yellow paint had been completely removed. I was delighted to notice the fake window that had been painted in, to preserve the continuity. Originally, it must have been done with stencils, so they’ll have to have new ones made. The downside of that paint job is that it’s more intricate and takes meticulous application, (and therefore is much more expensive) as opposed to the plain yellow. I have to confess, I did like the cheery, sunny yellow.